EU legal fight against human trafficking | January 20, 2014 ICRP

Migration

has always been part of Europe’s history. It is a social phenomenon that

has largely influenced the outlook of the present-day European Union.

People from or to Europe have migrated because of various reasons

including poverty, oppression, discrimination, persecution, war, natural

disasters, unemployment, vision of better living conditions, etc. We can

assume, that particularly in recent decades, migration in Europe has

mostly been seen in the form of immigration into Western European states

from poorer Eastern or South-eastern parts of Europe, Middle East or

developing African countries.

Migration

has always been part of Europe’s history. It is a social phenomenon that

has largely influenced the outlook of the present-day European Union.

People from or to Europe have migrated because of various reasons

including poverty, oppression, discrimination, persecution, war, natural

disasters, unemployment, vision of better living conditions, etc. We can

assume, that particularly in recent decades, migration in Europe has

mostly been seen in the form of immigration into Western European states

from poorer Eastern or South-eastern parts of Europe, Middle East or

developing African countries.

Most visible result of immigration is proven to be the fact that many EU countries comprise large immigrant communities coming from all over the world. Over the years, immigrant groups became an integral part of the European society. However, nowadays, the immigration question is becoming more and more sensitive in Europe. Many Western European states have to cope with the huge influx of immigrants and refugees from war-torn countries. The immigration policies of receiving states often struggle with fulfilling integration of immigrants to majority societies. On one side, immigration offers great possibilities and advantages for both immigrants and receiving states. On the other side, it is a difficult process that also brings many traps and challenges that the states have to cope with. This applies in particular to immigrants who enter the certain state illegally, to problematic immigrant groups that usually move to more advanced countries with the aim to abuse the social welfare system of the receiving country, or to ones who seek to benefit from criminal activities. The latter mentioned group is considered the most dangerous for the state’s security and calls for most attention from the European authorities. The free movement of persons within EU borders, which is one of the key principles guaranteed by the EU, does not only facilitate migration procedures, but also makes it more difficult to control activities of organised criminal groups. The organised crime means danger to human security, as it threatens lives and well-being of individuals. Besides, it also harms the state as a whole including its security balance, economy or international relations and poisons the entire EU system. Undoubtedly, one of the most alarming and harmful forms of carrying out organised crime is trafficking in human beings, which has a vigorous moral element. Therefore, fight against organised crime in general and especially against human trafficking, belongs to one of the top priorities of the EU.

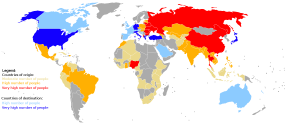

Trafficking in human beings as part of organised crime is in many aspects considered a modern-day slavery. There is no doubt that it is a global problem, as virtually every single state in the world is affected, either as a country of origin, transition or destination. Nowadays, human trafficking occurs greatly in the form of a transnational organised crime, but it still occurs also on the domestic level, within one state. Pursuance of trafficking in people as if they were inanimate material goods intended for sale and service is an act against human dignity and a grievous violation of fundamental human rights.

We can note, that there are several significant institutions both on international and European level, having an eminent role in fight against human trafficking, either speaking about the UN, NATO, EU organs, organisations from non-governmental area or academic field. Within the UN, we can specifically point out the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) which operates on the global scale and one of its most urgent agendas is human trafficking and migrant smuggling. The UNODC developed the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, that is the leading UNODC document in fight against trafficking. The paragraph (a) of the article 3 of the material defines human trafficking as: “recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.” As the definition indicates, there are several types of human trafficking, divided based on purpose for which the victims are needed for. To analyse the problem more in depth, in this context, we can differentiate between sexual exploitation, that usually targets women and children and includes prostitution, trafficking in brides, sex tourism or pornography production. Sexual abuse is followed by the second most frequently occurred economic exploitation, which involves servitude or forced labour performing like begging, illegal work in factories, domestic work or illicit sales. The third category focuses on children, mainly in the form of their illegal adoption or their use for child soldiering. The last but not the least is the removal of organs and body parts.

Regarding definition, it is also important to note, that despite there are significant overlaps in the meaning of trafficking and smuggling, it is necessary to distinguish between these two terms. While smuggling means rather providing certain paid service for immigrants, usually referring to help them illegally enter desired country, trafficking does not end when having crossed the borders. Victims of trafficking do not know about their future exploitation since they are misled, immorally abused and treated as only simple means to earn money for perpetrators. According to International Labour Organisation (ILO), almost 21 million people worldwide are being exploited for labour purposes, including human trafficking. Only in the EU, the estimated figures climb to 1 million of victims. In 2010, trafficking in human beings was the “fastest growing criminal industry” and the third most expanded criminal business after drugs and military equipment. The statistics prove that the human trafficking issue is indeed at least worrisome.

The even more anxious fact is, that the large majority of offences is uncovered and thus it is not possible to accuse the perpetrators. For example, in 2007, “there were only 5,682 prosecutions and 3,427 convictions for trafficking throughout the world. This means that for every 800 people trafficked, only one person was convicted in 2007.” Not surprisingly, EU Member States have indicated human trafficking as one of the key spheres in the fight against organised criminal groups. This argument is plausibly proven by the fact, that “among the new initiatives, the European Council in Stockholm has adopted so-called Stockholm programme in December 2009 making the fight against human trafficking a main concern for the Union.” The programme is designed for the period from 2010–2014 and its major objective is to set common goals and thus improve coordination with the third countries which are in many cases places of human trafficking’s origin.

Likely most weighty EU organ in the fight against trafficking is considered the European Commission, that proposed the Directive 2011/36/EU on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims, which is currently the most relevant EU anti-trafficking legislative document. For better illustration of the newest Directive’s background, it is needed to specify also prior legal documents. The predecessor of Directive 2011/36/EU is composed of three legal instruments, namely of Council Directive 2004/81/EC, Council Framework Decision 2001/220/JHA and Council Framework Decision 2002/629/JHA, of which all are focusing on certain areas of protection and prevention. The main feature of the Council Directive 2004/81/EC is the demand directed to Member States to grant residence permits to trafficked individuals coming from non EU countries who collaborate with responsible organs. The second major document, Council Framework Decision 2001/220/JHA adopted in 2001, concentrates on any criminal offences falling under national law of EU Member States. The last legislative instrument, generated in 2002, stresses the necessity to investigate and accuse perpetrators of trafficking and the need for a an effective criminal law structure. This document was intended to be replaced by the new Directive.

The Directive 2011/36/EU came into existence as a result

of the need and the demand and was adopted by the European Parliament

and the Council. Being the latest action of the EU in the field of human

trafficking, the Directive aims to build up a comprehensive and more

efficient anti-trafficking policy. According to a Joint UN Commentary,

“the adoption of the 2011 Directive on preventing and combating

trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims, replacing

Council Framework Decision, is the most recent sign of the continued

commitment of the European Union in this field. The Directive represents

a critical step in addressing human trafficking comprehensively.“ There

are several innovative aspects of the Directive in comparison with

previous legal materials. These factors promise more efficient legal

basis for tackling the human trafficking problem. While creating key

principles of the Directive, the European Commission focused on more

thorough prevention, prosecution of criminals and protection of victims

based on a gender, victim-centered and human rights’ approach. The human

rights’ perspective is primarily embodied in the section that deals with

help, support and assistance for victims. The principle of the

protection of trafficked is also amended, in particular with regard to

criminal proceedings, at which the victims often need to take part. The

main objective in this field is to prevent mainly children from fear or

distress when encountering with the offender that may result in

secondary victimisation and that could leave negative consequences on

psychological condition of victims. It is primarily emphasized, that

victims are in need of material and psychological help especially when

it comes to proceedings. The assistance should also include legal

counselling and interpreters. On the other side, there is a high

probability that the provision of assistance will not continue also

after completion of the criminal proceeding. Later on, the character and

extension of support remains within individual Member States. As stated

in the Article 12, greater assistance can just be provided in the

framework of the criminal justice system. Regarding one of the main

principles of the document which is the prosecution of perpetrators, the

Directive brings the possibility to prosecute EU citizens for crimes

perpetrated in the third countries. The Directive also devotes special

attention to various forms of trafficking and to valid means of their

facing. Further, the document takes into consideration that human

trafficking, likewise other phenomena, unfortunately has been evolving

and developing. That is why it is necessary to respond with at least

similarly developed means to prevent this crime. This includes also the

levels of penalties in the Directive, which are adapted on the basis of

certain factors present when the crime is committed. For instance, when

the victim is considered especially vulnerable (children, pregnant

women, etc.), the penalty should be considerably stricter.

The Directive 2011/36/EU came into existence as a result

of the need and the demand and was adopted by the European Parliament

and the Council. Being the latest action of the EU in the field of human

trafficking, the Directive aims to build up a comprehensive and more

efficient anti-trafficking policy. According to a Joint UN Commentary,

“the adoption of the 2011 Directive on preventing and combating

trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims, replacing

Council Framework Decision, is the most recent sign of the continued

commitment of the European Union in this field. The Directive represents

a critical step in addressing human trafficking comprehensively.“ There

are several innovative aspects of the Directive in comparison with

previous legal materials. These factors promise more efficient legal

basis for tackling the human trafficking problem. While creating key

principles of the Directive, the European Commission focused on more

thorough prevention, prosecution of criminals and protection of victims

based on a gender, victim-centered and human rights’ approach. The human

rights’ perspective is primarily embodied in the section that deals with

help, support and assistance for victims. The principle of the

protection of trafficked is also amended, in particular with regard to

criminal proceedings, at which the victims often need to take part. The

main objective in this field is to prevent mainly children from fear or

distress when encountering with the offender that may result in

secondary victimisation and that could leave negative consequences on

psychological condition of victims. It is primarily emphasized, that

victims are in need of material and psychological help especially when

it comes to proceedings. The assistance should also include legal

counselling and interpreters. On the other side, there is a high

probability that the provision of assistance will not continue also

after completion of the criminal proceeding. Later on, the character and

extension of support remains within individual Member States. As stated

in the Article 12, greater assistance can just be provided in the

framework of the criminal justice system. Regarding one of the main

principles of the document which is the prosecution of perpetrators, the

Directive brings the possibility to prosecute EU citizens for crimes

perpetrated in the third countries. The Directive also devotes special

attention to various forms of trafficking and to valid means of their

facing. Further, the document takes into consideration that human

trafficking, likewise other phenomena, unfortunately has been evolving

and developing. That is why it is necessary to respond with at least

similarly developed means to prevent this crime. This includes also the

levels of penalties in the Directive, which are adapted on the basis of

certain factors present when the crime is committed. For instance, when

the victim is considered especially vulnerable (children, pregnant

women, etc.), the penalty should be considerably stricter.

In order to effectively implement the system of EU laws on human trafficking, notably the Directive 2011/36/EU, the EU Strategy towards the Eradication of Trafficking in Human Beings 2012-2016 was consequently adopted by the European Commission. This EU Strategy can be identified as a collection of specific measures that were elaborated in order to help the states to implement the Directive and thus partially accomplish the principal objectives of its mission. These measures should be applied with a close cooperation with other significant actors, including “Member States, European External Action Service, EU institutions, EU agencies, international organisations, third countries, civil society and the private sector.” The time frame for its implementation is five years. The EU Strategy is practically based on five key fundamentals whose following is, according to EU authorities, important for the success of the EU anti-trafficking policy. These keystones are:

“A. Identifying, protecting and assisting victims of trafficking

B. Stepping up the prevention of trafficking in human beings

C. Increased prosecution of traffickers

D. Enhanced coordination and cooperation among key actors and policy coherence

E. Increased knowledge of and effective response to emerging concerns related to all forms of trafficking in human beings”.

It is inevitable to note, that the Directive should have been fully transposed by the EU Member States until 6 April 2013. By this deadline, states were committed to address necessary alterations within national legal frameworks in order to be able to fully implement the provisions of the Directive. Notwithstanding, not all the states met the full scale of required conditions. For example, “the UK government has been criticised for failing to adopt and implement legislation and practice to fully meet its obligations under the Directive,” which is a rather worrisome fact. Based on the recent information, the UK ultimately managed to transpose the Directive, but more than half year after the stated deadline and despite formal request from the European Commission, there still were states that have not met their obligations under EU anti- trafficking legislation. These states were specifically Spain, Italy, Cyprus and Luxembourg. The European Commission expressed its concerns and hope that these mentioned states will become active actors of the common EU anti-trafficking policy as soon as possible.

The problem of human trafficking is an alarming issue that justifiably became one of the central priorities of the EU policy. Its solving or at least moderating its grievous consequences requires an active and efficient approach from the side of European authorities, as well as individual Member States. Despite the enormous effort of the EU to tackle the human trafficking problem with the most valid and virtual practices possible, we can conclude, that there still are certain shortcomings of the EU anti-trafficking policy, in particular concerning the implementation of the Directive 2011/36/EU into legal systems of EU Member States. This argument is proved and justified by the fact that despite the firmly stated deadline of the Directive’s transposition, there was a number of states that did not comply with their obligations in this perspective. The reality is, that notwithstanding the active efforts by the wide international community to combat criminal activity of the traders in human beings, the statistics reveal that the number of trafficked for different purposes is still growing across the EU. Competent authorities should therefore give greater emphasis to cooperation in order to boost the development of more effective anti-trafficking instruments.

* * *

-icrp-