Legal discrimination against native women in Canada | July 22, 2014 ICRP

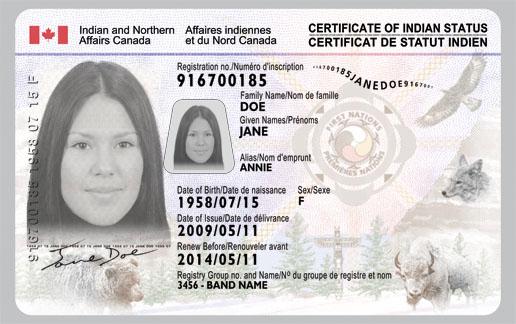

Government-issued Indian

Status card.

Image courtesy of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.

Legal

and sexual discrimination against Native American people has always been

strong in Canada. However, it is Native American women who belong to one

of the most marginalized groups in the country. Radically saying, the

government managed to create a social system in which indigenous women

are at the bottom. The strongly discriminating Canadian Indian Act of

1951 provided the basis for this social hierarchy.

Legal

and sexual discrimination against Native American people has always been

strong in Canada. However, it is Native American women who belong to one

of the most marginalized groups in the country. Radically saying, the

government managed to create a social system in which indigenous women

are at the bottom. The strongly discriminating Canadian Indian Act of

1951 provided the basis for this social hierarchy.

The 1951 version of the Indian Act is a revision of the legal statute passed in 1867. It begins with the following sentence: “An Act respecting Indians”. Nevertheless, one can hardly find true respect in the act, which manages to colonize indigenous peoples through the letter of the law. When reading the Canadian statute, it becomes clear that the act is in fact creating an unequal power relationship between indigenous peoples and the white nation-state. With the enactment of the Indian Act, the government defined every aspects of native life: political, geographical, and personal. The statute constructed the system of the band councils, marked off spaces as reservations (the ‘right’ place for an Indian to live), but most importantly it defined who is an Indian, which is in itself a controversial issue since a group of people, who is not indigenous, defines what it means to be an Indian.

Reading the statute we can clearly see that it is discriminating against native women at several points. The most strikingly discriminating sections are the definition of an Indian, the rules of marrying, of land ownership, and the discussion of voting rights. The definition of Indianness states that only male persons of Indian blood who lives on a specific land counts as an Indian. One can wonder then whether where can we situate native women according to this definition? The law later gives an answer: it considers a female indigenous person to be a ‘real’ Indian only if she is legally married to a male person who fits into the definition of an Indian.

The section discussing the rules of marriage clearly states that if a native woman marries a white man, she will lose her rights and no longer be considered an Indian. Moreover, if an indigenous woman marries a man who is a member of another band, she will no longer be a member of the band to which she formerly belonged and becomes the member of her husband’s. The fact that the statute does not clarify the title of women who marry a white man conveys the impression that they do not enjoy any rights – that would be guaranteed to them due to their indigenous background – as a consequence of outmarriage. As we can see, this section situates native women into a heavily dependent position, as their identities are contingent on their husbands’. Male members are therefore in control over their mere existence. This section was changed by an amendment in 1985, saying that after outmarriage, a native woman is entitled to keep her status.

The Indian Act does not clearly states that only male natives can own a land, but when it defines land ownership it only refers to men implying that female natives may not be in possession. The text is continuously using the personal pronoun ‘he’. Indigenous women are seemingly not entitled to be owners of a land, which automatically means that they do not have social (and political) power, for according to Western conceptualization private property is a significant part of determining one’s identity. In the Western world, it is private property that first warns inclusion into society and second gives power to the individual.

According to the Indian Act only male members of a band are able to apply for being enfranchised. Female Indians might have the right to vote in one way: if a male Indian possesses the right to vote, it automatically enfranchises his children and his wife. However, if the wife lives apart from his husband this possibility does not apply. A wife living apart from her husband may get the right to vote but only if she submits a request to the government. Therefore, the political rights of native women also depend first on their husbands and second – if living apart – on the decision of the male dominated government.

The act continuously differentiates between male and female native people and makes indigenous women dependent on their husbands. The text is highlighting that indigenous women have different – and less – rights than indigenous men. All these sections contributed to the procedure in which indigenous women were turned into wards of native and white males.

Native women had to – and still have to – face the consequences of the discriminating nature of the Indian Act. The main phenomena brought about by the statute are completing each other. As the statute is questioning the moral character of native women at several points a negative stereotypical image was fabricated: the image of the indigenous woman, who has no sexual morality at all. This stereotypical representation led to the belief that indigenous women deserve abuse because they are inherently promiscuous. Their bodies became something to be ruled over. As a result of this, using violence against native women became normative.

The main reason for the creation of the image of the sexually immoral Indian woman was mainly the desire of white society to be seen as different. This image making was instrumental in creating a boundary between white and native society. The process of image making started in the 1880s when more and more stories about the inefficiency of government officials spread. Their reputation was tarnished by stories of sexual abuse committed by officials against families that were in need. The agents had to hide their own sins and therefore they spread the image of the sexually immoral native woman to rebuff criticism of agents and policies. The false representation managed to cover everything that white men committed against indigenous women, as they were proclaimed as immoral and therefore it got little attention if a white man abused an indigenous woman.

In addition, more and more white women arrived to Canada in the end of the 19th century. Their moral way of life was contrasted to the immoral indigenous women’s habits. Female indigenous existence came to symbolize what is it not to be a white woman. The main belief was that native traditions are the reason for the ongoing corruption and violence on the reservations. The negative image was used to represent white population as the example of morality. It differentiated white people from indigenous people – especially women – in order to secure power over them. The white settler nation symbolized the moral civilized world and took up the role of a saviour, who will lead indigenous nations to civilization.

As this image was more and more promoted it contributed to another phenomenon. Sexual violence against native women was seen as a norm. The misrepresentative image of immoral native women went hand in hand with the belief that when they became victims of violence, indigenous women got what they deserved. Men who abused native women were not seen as criminals because abusing indigenous women was not considered as abnormal. On several occasions when native women complained, the police did not deal with the issue claiming that their complaints were mere fiction. The bodies of these women were made completely vulnerable and available to men at any times.

One important fact appears here. White men played a significant role in this control securing. The nation state and its white citizens were in a reciprocal relationship. The government secured the bodies of native women – by creating a degrading image of them and obliquely accepting sexual violence as a norm – to violent white males who in return did the dirty job: physically and emotionally destroyed indigenous women. The nation state indirectly supported white men to maintain their sense of identity through brutality while the action of men helped to establish the nation state’s dream: a purely white society, where indigenous people are invisible.

* * *

-icrp-